Canopies for tjes-bastet-peret with lid with different shapes © KHM Museum Association

Mummy board from Nes-pauti-taui © KHM Museum Association

Inner coffin of Nes-pauti-taui © KHM Museum Association

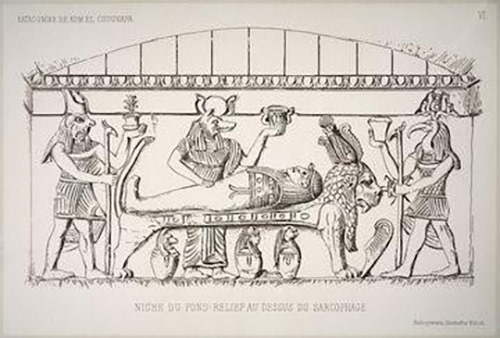

Fotografische Reproduktion der von E. Gilliéron hergestellten Tafel VI aus: F.W. von Bissing: La catacombe nouvellement découverte de Kom el Chougafa (1901) Institut für Kunstgeschichte der Universität Wien, Fotosammlung

The European interest in Egyptian mummies mainly started in relation to the techniques and substances of the embalming process. In the beginning, the possible use of Egyptian mummies for the production of medicines was in the foreground. Thus, until the end of the 19th century, "mummy powder" could be purchased in European pharmacies for indigestion. Sensationalism characterised the curiosity and travel reports and the interest in the production process of mummies in the 17th century. In the 18th century, the mummy was a popular collector's item, but in the 19th century this took on a new dimension and a veritable "Egyptomania" broke out. As a result, European museums and collections competed for the oldest and most beautiful mummies and coffins. In Great Britain, moreover, mummies were publicly unwrapped and dissected for entertainment purposes in the 1830s. Then, at the end of the 19th century, Egyptian authorities began to prohibit the trade in and export of mummies.

In 1835, Egypt issued a decree stating that antiquities could only be exported with an official permit. It was also ordered that any artefacts found in the future must be taken to the Egyptian Museum. The theft and sale of several mummies from 1871 onwards led Egypt to further tighten regulations on the sale and export of ancient objects, and a 1891 decree allowed excavations only if official permission had been granted beforehand. At the same time, however, foreign excavations were allowed through the system of partage to export part of the finds after an official permit had been granted. Penalties and restitution to Egypt were established for excavations without permits. After increasing cases of smuggling in the 20th century, the penalties for smuggling were increased in 1951. From then on, export permits could only be issued officially in consultation with experts. In 1983, it was finally decreed that all monuments and artefacts excavated in Egypt were the property of Egypt, which abolished the previously common system of partage.

Egyptologist Salima Ikram emphasises that the heyday of collecting and acquiring Egyptian artefacts took place in the imperialist, colonial 19th and early 20th centuries. That is, at a time when the "culture" of colonized groups was either considered "inferior" or their imagery was appropriated. During this period, Egypt was under Ottoman rule. They viewed ancient objects from an economic point of view and offered them for sale as host gifts and potential goods. As a result, Europeans considered Egypt as their personal hunting ground for ancient artefacts. All kinds of objects were shipped to the "West" on a large scale. Most of the major museums in Europe and North America have large collections of Egyptian objects. They mostly originated in the cabinets of curiosities of the aristocracy, who had objects purchased by dealers.