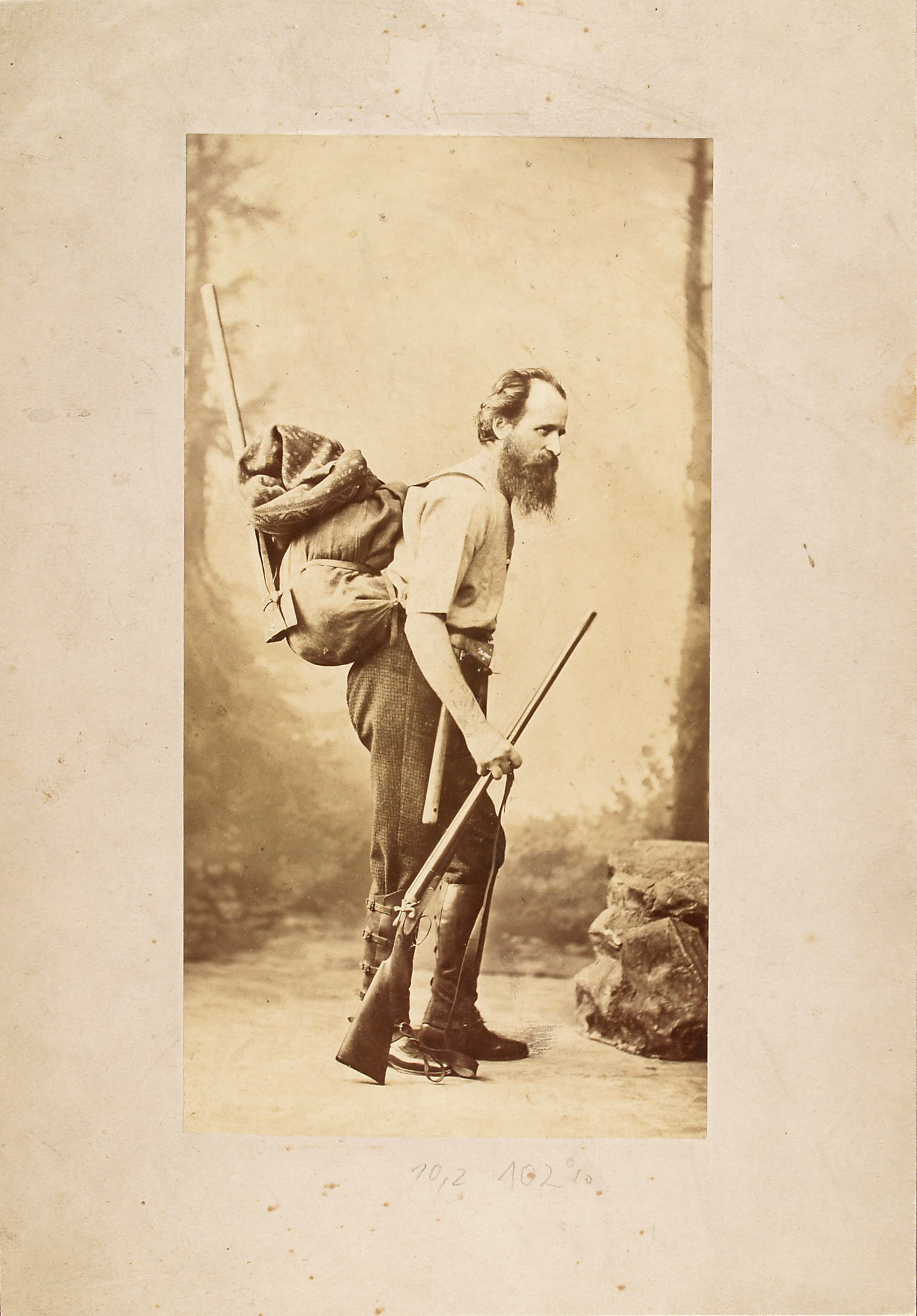

Andreas Reischek with his expedition equipment around 1890. Vienna World Museum, photo 51.564

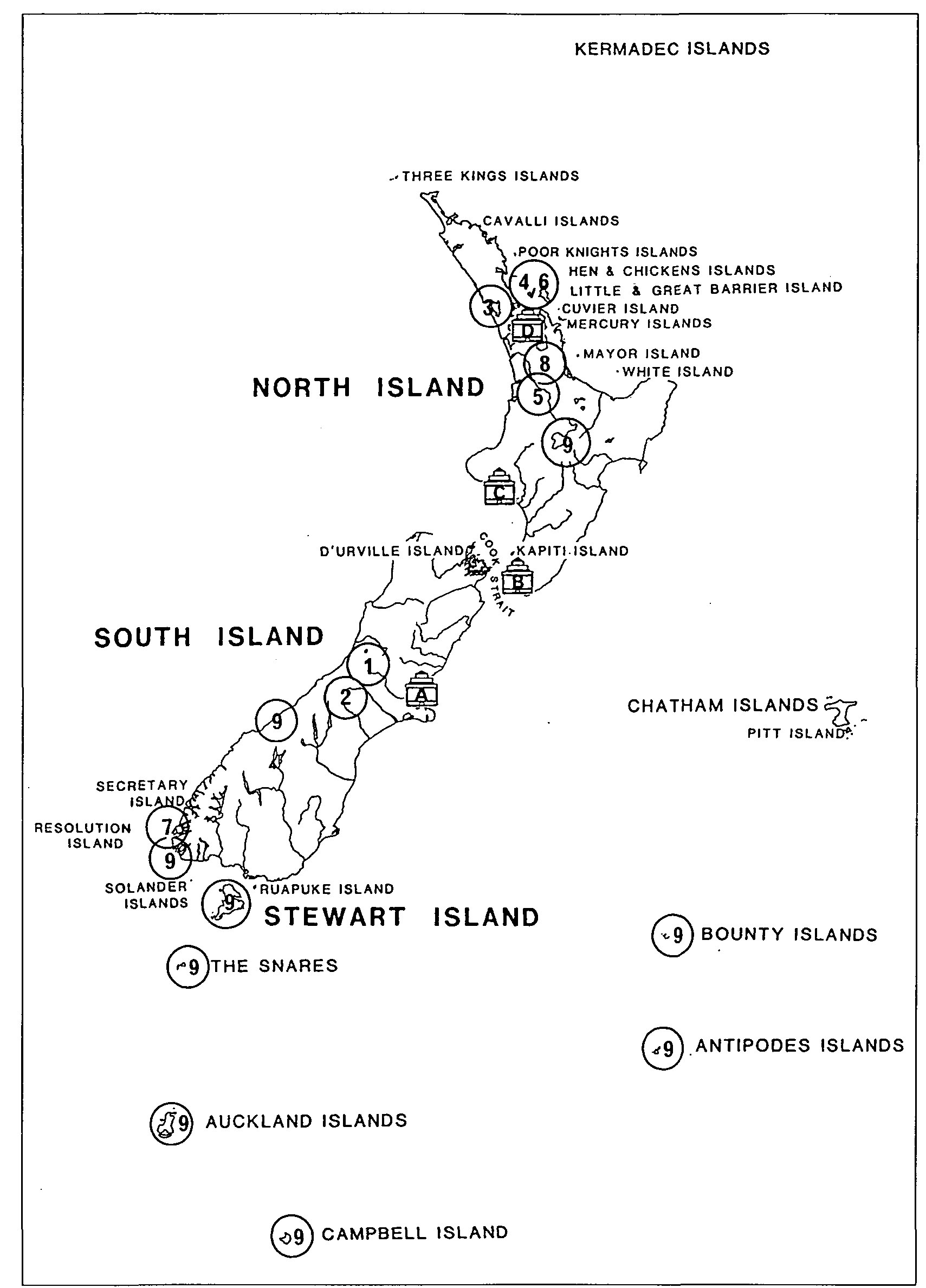

Map of New Zealand showing Reischek's Expeditions 1 - 9 and his work sites (A = Christchurch, Canterbury Museum; B = Wellington, National Museum; C = Wanganui, private museum; D = Auckland Museum). Graphic: S. Weigl

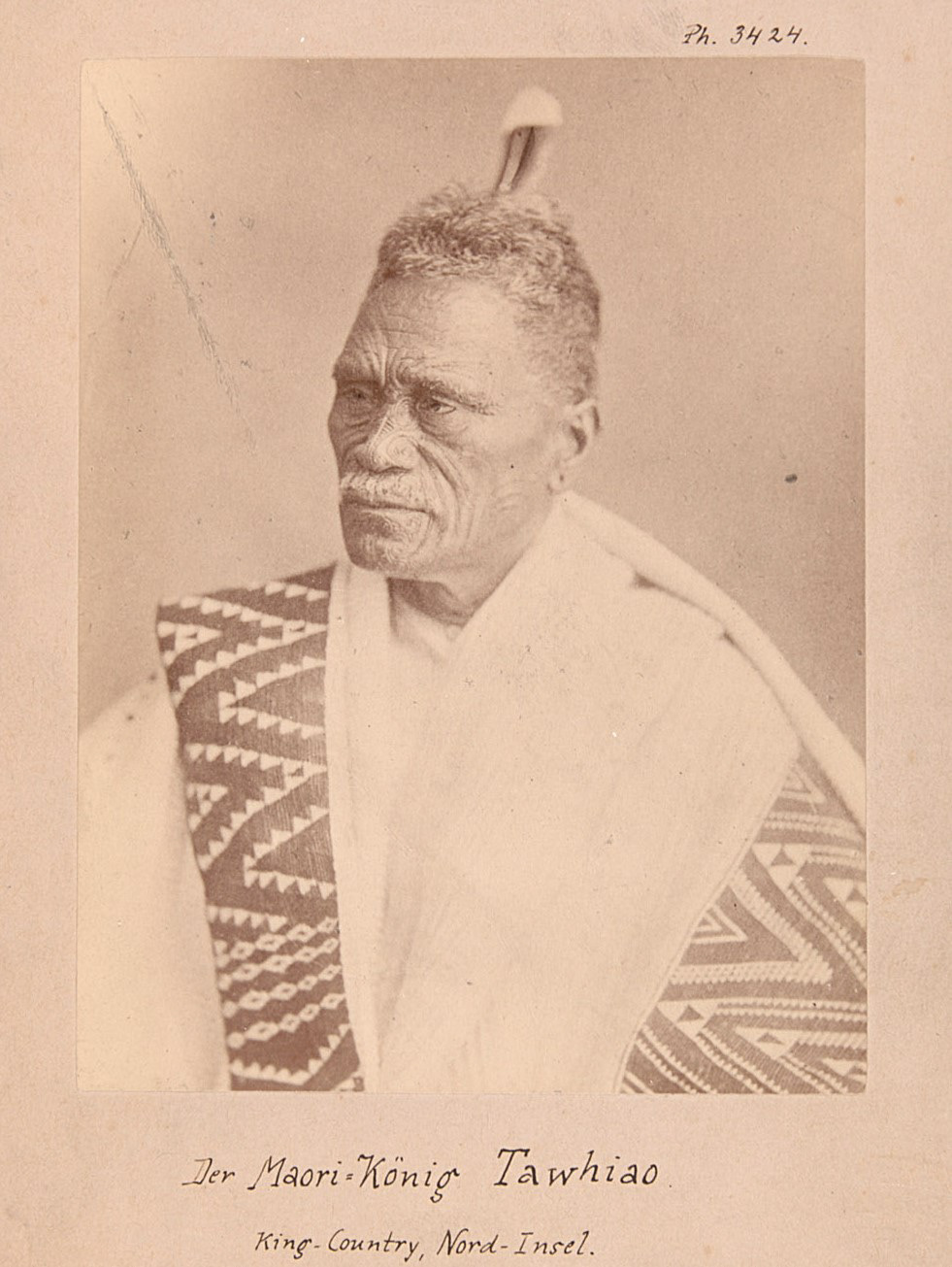

Tawhiao, the Maori king, dressed in a kaitaka in Whatiwhatihoe King Country, North Island of New Zealand. (Collection Andreas Reischek). Vienna World Museum, photo 3.424

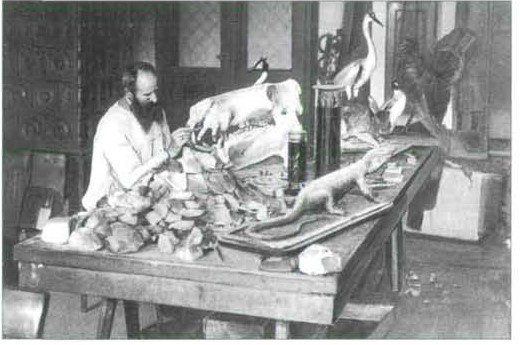

Reischek at work in the taxidermy of the Francisco-Carolinum Museum. Archive Upper Austria. State Museum

Andreas Reischek, custodian, Museum Linz, sitting around 1890. Vienna World Museum, photo 51.563

Andreas Reischek Jr. (ed.) 1924. Dying World. Twelve years of explorer life in New Zealand. Brockhaus Publishing House

"Two Maori, already European enough to deny their national and religious principles for money, led me at night to a cave near Kawhia; there I found four mummies, two of which were immaculately preserved.

The enterprise was very daring, for its discovery would infallibly have cost me my life. During the night the mummies were carried on, then well hidden; the next night they were carried on again until I had brought them across the border of Maoriland. But even there I kept them hidden as a precaution until my departure. Now these two Maori ancestors adorn the ethnographic collection of the Vienna State Museum of Natural History." (Reischek 1924: 174f)

Andreas Reischek comes from Linz in Upper Austria and was originally a baker. He learned taxidermy on his own and worked in Vienna as a taxidermist and dealer in teaching aids. Ferdinand Hochstetter (1829-1884) of the Vienna k.k. Natural History Court Museum got him a job as a taxidermist and collector with Julius von Haast, director of the Canterbury Museum in Christchurch, New Zealand, which Reischek took in 1877. He collected artifacts for museums in Auckland, Wellington, and Wanganui. Reischek spent a total of twelve years in New Zealand, independently exploring the island and collecting more objects. To finance his stay, he sold and traded collection items. He maintained friendly relations with the Maori, especially with King Tawhiao, who gave him access to the king's land, which was closed to Europeans. In 1889 Reischek returned to Austria. He did not receive the recognition he had hoped he would for for the scientific collection he had brought with him. On nine expeditions, he collected 1200 ethnographic objects, 37 human skulls and 2 Maori mummies. He also brought to Austria self-made specimens of 3000 birds, 120 mammals, 800 fish and reptiles, 2500 plants and numerous geological and mineralogical samples with him back to Austria. 500 objects came from New Zealand, others from Australia and other Pacific areas. From 1892 he worked as a curator and preparator at the Francisco-Carolinum Museum in Linz. Through a donation by banker Carl von Auspitz, Reischek's natural history collection was bequeathed to the Natural History Museum in Vienna, and the Maori objects and human remains to what is now the Vienna World Museum. The Maori skulls remained in the anthropological collection of the Natural History Museum.

Reischek is criticized today for his collecting methods. He robbed with the support of native Maori, tools, jewelry, carvings, human bones, skulls and two mummies from ancient forbidden burial caves and brought them to Europe. Researcher Erich Kolig (1998: 47) opines:

“His zeal for collecting and his attitude manifested therein that the (scientific) end justifies the means, had all too often led him to disregard all scruples, feelings of tact and loyalty towards his Maori friends and - from today's point of view - to pursue his goals with astonishing cold-bloodedness and brutality.”